Our Vision

Taylor Geospatial is a new nonprofit organization focused on democratizing the power of GeoAI through global partnerships while strengthening innovation capacity in the St. Louis region.

Ideas to Impact

Bridging the gap between breakthrough academic research and real-world industry deployment, to accelerate the transition from idea to impact.

Collaboration for Scale

Actively co-developing and co-investing with leading GeoAI contributors–satellite operators, cloud providers, foundation model developers, and prominent research labs.

Open Pipelines

We build an ecosystem to democratize access to global scale labels, models, embeddings, and datasets that enable researchers, entrepreneurs, companies, and governments to create geospatial insights and accelerate commercialization.

Initiatives

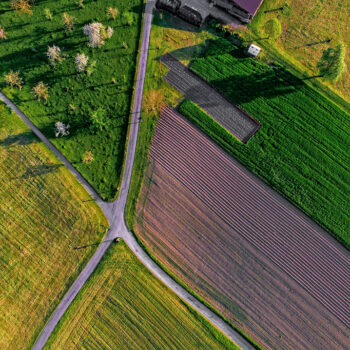

Fields of the World

Fields of The World is a groundbreaking program designed as an “innovation bridge” between academic research and industry. In its first phase, FTW released the largest benchmark dataset for training models to infer field boundaries from satellite imagery. In its second phase, FTW released an assessment of over 70 geospatial AI models and their comparative performance, in addition to releasing a high performing model architecture for inferring global field boundaries. By making this ecosystem openly available, we’re empowering researchers, NGOs, and governments to better understand and manage agricultural systems worldwide.

Geospatial Innovation for Food Security

Taylor Geospatial convened a transdisciplinary community of researchers, innovators, and implementers to identify critical challenges in food security and sustainable agriculture that could be addressed through geospatial innovation. We launched the Geospatial Innovation for Food Security Challenge to support advanced research to address three of these challenges: enabling agri-food supply chain resilience, informing crop shifting, and increasing nitrogen use efficiency.

Our Team

Join Our Community

Interested in collaborating or partnering on open geospatial research initiatives, or learning more about our work in advancing GeoAI for the digital public good?

Whether you’re a researcher, service provider, organization, or community leader, we’d love to hear from you and explore how we can work together to accelerate deployment and development of breakthrough geospatial solutions.